My article ‘ “Hitler had a valid argument against some Jews”: repertoires for the denial of antisemitism in Facebook discussion of a survey of attitudes to Jews and Israel’, which was published online in April this year, has now appeared in the August issue of Discourse, Context & Media. It explains the background to the antisemitism crisis that has now engulfed the Labour Party leadership, then analyses some of the ways in which Labour supporters deny the existence of antisemitism before looking at how the largest unofficial Labour Party Facebook group makes the problem worse by readily expelling those who challenge antisemitism but only expelling antisemites for extreme transgressions.

Tag: research

Voters in the 2017 general election – and how they voted previously

This is the third and final part of my preliminary analysis of groups of voters defined by the choices they made in the 2015 general election, the 2016 European Union membership referendum, and the 2017 general election (c.f. Stephen Bush’s nine voter groups), using an English subset of responses to the British Election Study’s post-election face-to-face survey. In the first part, I looked at the ten largest groups, from Conservative-Leave-Conservative to Conservative-Remain-Labour, both in terms of their size and in terms of their self-declared likelihood to vote for various parties in future, and found that Labour Remainers were not only more numerous but (on their own assessment) more likely to be poached than Labour Leavers, while the smaller group of Conservative Remainers who had switched to voting Labour were quite likely to switch again. In the second part, I looked at six groups of voters who had in common that they could have voted but did not in the 2015 general election, finding that most of them did not vote either in the 2016 referendum or the 2017 general election, and that only the minority who voted Remain in the 2016 referendum were more likely than not to have voted in the 2017 general election.

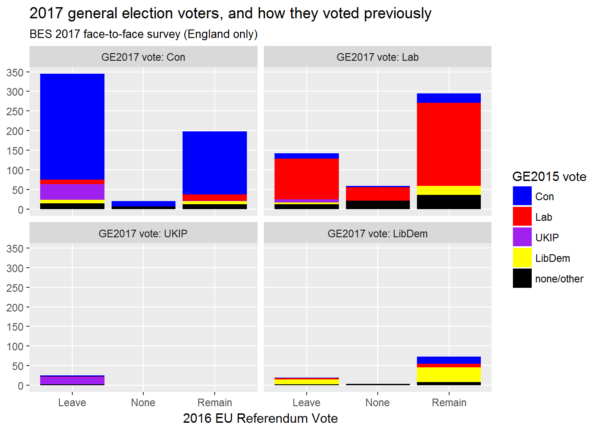

To finish up for now, here’s a single chart showing all voter groups which participated in the 2017 general election (weighted by demographic group and by 2017 vote). Each quarter of the chart below shows the members of the sample who voted for one of the four main parties. These voters are further subdivided into columns to show how they voted in the referendum and into coloured blocks to show who they voted for in 2015 (note that black covers both non-voting and voting outside the four main parties, which most often meant voting Green as the data are from England only):

Continue reading “Voters in the 2017 general election – and how they voted previously”

Ten voter groups: combinations of EU referendum and general election votes in the BES 2017 face-to-face survey

Like many, I read with interest Stephen Bush’s recent article on ‘The nine voter groups who are more important than Labour Leavers’. If Bush were a grant awarding institution, there would be money available for researching those groups. Well, he isn’t, so there isn’t, but I like a challenge so I’m going to make a start anyway – using open data from the British Election Study (henceforth, BES). To be more specific, I’ll be using the BES 2017 face-to-face survey, which was conducted after the election and uses what should probably be considered a more genuinely random sample than the online waves.

‘Hitler had a valid argument against some Jews’: repertoires for the denial of antisemitism in Facebook discussion of a survey of attitudes to Jews and Israel (manuscript draft)

This manuscript has been accepted for publication in the peer-reviewed academic journal, Discourse, Context & Media. By agreement with the publisher, it can be distributed on this website. For offline reading, a PDF copy is available for download (although if you wish to share it with others, please direct them to this page rather than sending the file directly). EDIT (13 April 2018): The version of record is now available online via ScienceDirect at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2018.03.004 ahead of print publication. EDIT (4 August 2018): The article has appeared in the August issue of Discourse, Context & Media (vol. 24), and is available online at the same address (although now with correct pagination).

Author: Daniel Allington, University of Leicester

Journal: Discourse, Context & Media

Received at editorial office: 11 Dec 2017

Article revised: 16 Mar 2018

Article accepted for publication: 21 Mar 2018

Article available online via ScienceDirect: 12 April 2018

Article available in print: 21 July 2018

Bibliographic reference: Allington, D. (2018) ‘ “Hitler had a valid argument against some Jews”: Repertoires for the denial of antisemitism in Facebook discussion of a survey of attitudes to Jews and Israel’. Discourse, Context, and Media 24: 129-136.

Abstract

Discourse analytic research suggests that, in contemporary liberal democracies, complaints of racism are routinely rejected and prejudice may be both expressed and disavowed in the same breath. Historical and quantitative research has established that – both in democratic states and in those of the Soviet Bloc (while it existed) – antisemitism has long been related to or expressed in the form of statements about Israel or Zionism, permitting anti-Jewish attitudes to circulate under cover of political critique. This article looks at how the findings of a survey of anti-Jewish and anti-Israeli attitudes were rejected by users of three Facebook pages associated with the British Left. Through thematic discourse analysis, three recurrent repertoires are identified: firstly, what David Hirsh calls the ‘Livingstone Formulation’ (i.e. the argument that complaints of antisemitism are made in bad faith to protect Israel and/or attack the Left), secondly, accusations of flawed methodology similar to those with which UK Labour Party supporters routinely dismiss the findings of unfavourable opinion polls, and thirdly, the argument that, because certain classically antisemitic beliefs pertain to a supposed Jewish or ‘Zionist’ elite and not to Jews in general, they are not antisemitic. In one case, the latter repertoire facilitates virtually unopposed apologism for Adolf Hitler. Contextual evidence suggests that the dominance of such repertoires within one very large UK Labour Party-aligned group may be the result of action on the part of certain ‘admins’ or moderators. It is argued that awareness of the repertoires used to express and defend antisemitic attitudes should inform the design of quantitative research into the latter, and be taken account of in the formulation of policy measures aiming to restrict or counter hate speech (in social media and elsewhere).

Keywords: anti-Semitism; anti-Zionism; denial of racism; attitudes; Zionism; Israel; Jews; Labour Party; Facebook; social media

Importing National Student Survey data with R (or: how doing things programmatically helps to avoid mistakes)

I recently started to do some work with NSS (National Student Survey) data, which are available from the HEFCE website in the form of Excel workbooks. To get the data I wanted, I started copying and pasting, but I quickly realised how hard it was going to be to be sure that I hadn’t made any mistakes. (Full disclosure: it turns out that actually I did make some mistakes, e.g. once I left out an entire row because I hadn’t noticed that it wasn’t selected.) Using a programming language such as R to create a script to import data requires much more of an investment of time upfront than diving straight in and beginning to copy and paste but the payoff is that once your script works, you can use it over and over again – which is why I now have several years’ worth of NSS data covering all courses and institutions, from which I can quite easily pull out whichever numbers I want using a dplyr filter statement (as long as I am prepared to take account of irregularities e.g. in institutions’ names from one year to the next – which would also be necessary when doing things by point-and-click).

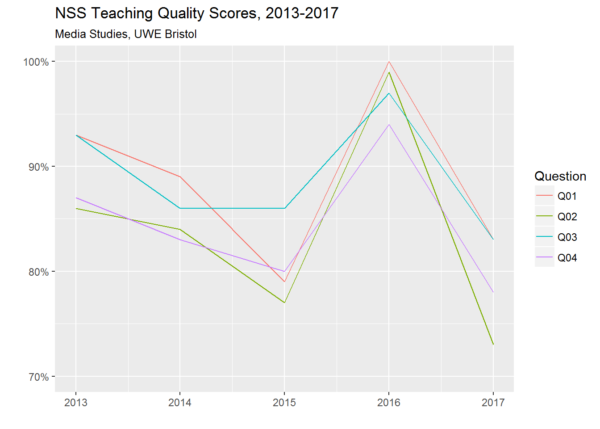

For example, looking at how all institutions performed in my particular discipline with regard to the four NSS questions relating to teaching quality, I can see that Media Studies at the University of the West of England managed the quite remarkable feat of rising from 68th place in 2015 to 2nd place in 2016 before falling back to 53rd place in 2017. To visualise only these four questions in relation to this subject at this institution over the whole time period for which I have data, I can filter out everything relating to other disciplines and other institutions with a single statement, and then use ggplot to represent each of the four variables that I’m interested in with a different coloured line:

How could such a dramatic rise and fall occur? Maybe someone who still works at UWE would be better placed to explain. But the general question of what drives student perceptions of teaching quality is one that I’m interested to explore as a researcher – and I’ll be posting thoughts and findings here as and when.

In the meantime, here’s my code, presented as an example of how the automation of error-prone tasks can take some of the uncertainty out of the research process. You probably aren’t interested in working with this particular dataset, but you may have other datasets that you would like to deal with in the same way. Yes, it looks complicated if you’re not used to scripting – but the code is actually quite simple, and the thing is that I was able to build it up iteratively, by adding statements, running the script as a whole, noticing what went wrong, and then fixing whatever it was, one step at a time. (The code is very heavily commented, to give a non-coder an idea of what those steps were and what sort of thinking is typically involved in taking a code-based rather than point-and-click-based approach to data importing etc.)

The unnoticed rise of the centrist voter (and what it means for Labour)

Centrist dads, eh? (And presumably also centrist mums, although abusing them on behalf of the Absolute Boy might sound less like striking a feminist blow against patriarchy.) How wrong they were! They were so sure that Labour was going to lose the election, when as everyone now knows… well, actually, Labour did lose, but never mind — the centrists were still wrong. Slugs! By refusing to compromise on his left wing principles, Jeremy Corbyn shifted the Overton Window, opened up some clear red water between Labour and the Tories, and flipped social liberals for Socialism. In losing the election by a mere 55 seats out of a possible 650, he achieved total vindication for his strategy, and proved that he only has to do more of the same in order to find himself at the head of the Government after the next election (unlike — say — Gordon Brown, who lost by 48 seats and resigned, the melt). Onward, comrades! Onward to Socialism!

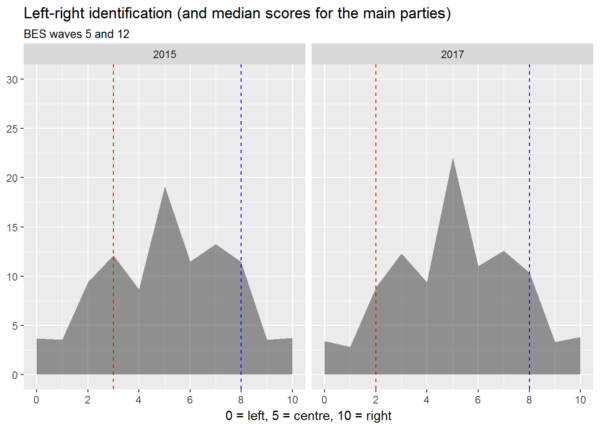

Now, I don’t believe that many people primarily choose whether or not to vote for a party to vote on the basis of how ‘left’ or ‘right’ they believe it to be. But ideas of leftness and rightness provide people with a way of summarising their relationships with political parties, and for this reason, I think it’s worth paying attention to the answers they give to survey questions about where they place themselves and the major parties on the left-right spectrum. And so we come to waves 5 and 12 of the British Election Study (or BES), in which a staggering 30725 and 34464 respondents took part immediately prior to the UK General Elections of 2015 and 2017. In the following chart, based on BES data, the grey areas show how people identified themselves, while the red and blue lines show how they typically situated the Labour Party and the Conservative Party on the same axis (respectively).1

Continue reading “The unnoticed rise of the centrist voter (and what it means for Labour)”

The left, the right, the centre – and what they care about most

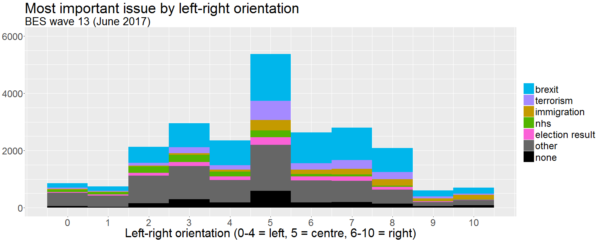

Why did people vote as they did in the June 2017 UK general election, and how might they vote in the next one — whenever it comes? One of the best sources of information on that question is wave 13 of the British Election Study: a very large survey conducted just after the election for a consortium of academics at the University of Manchester, the University of Oxford, and the University of Nottingham. Altogether 31196 respondents completed the survey, of whom 27019 (after weighting) answered the question ‘As far as you’re concerned, what is the SINGLE MOST important issue facing the country at the present time?’ and 23194 (again after weighting) identified themselves politically by positioning themselves on an eleven point scale from left to right. 21213 both placed themselves on the scale and gave their view on the most important issue. I’ve been working with this dataset for a little while, looking at how demographic variables predict perceptions of the most important issue (see my earlier post for my initial exploration of this topic), but here I’d like to focus on the association of particular issues with particular positions on the political spectrum:

Continue reading “The left, the right, the centre – and what they care about most”

Mapping the political Twittersphere

Public seminar by Daniel Allington

Starts: 16:00 15 Nov 2017

At: Mitchell Centre for Social Network Analysis, University of Manchester

Who follows British politicians on social media? Who stood with Ken Livingstone online? What would it be like to get all your political news from Twitter?

For over a year, I’ve been seeking answers to these questions and more using data scraping and a mixed methods approach centred on social network analysis. Social media have changed British political culture, creating quasi-celebrities out of figures who would otherwise have been condemned to the margins, and giving wide circulation to ideas long believed to be politically defunct – most alarmingly, the belief in an international conspiracy of Jews. In this seminar, I will present theoretical and methodological approaches to the large-scale study of online political culture, as well as sharing preliminary findings.

Open to all. Booking via the University of Manchester events website.

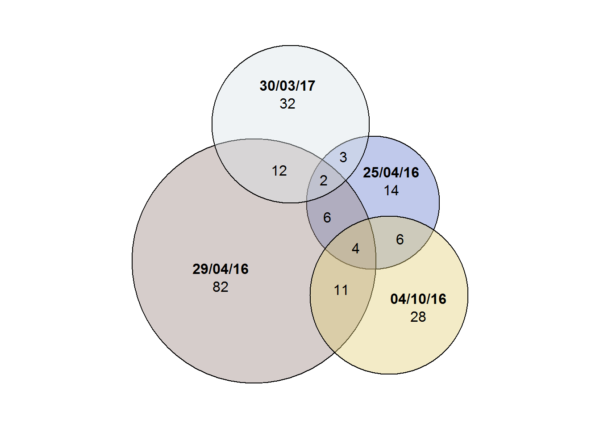

‘The usual suspects’: Euler diagrams of letter signatories as a practical application for set theory

The day before the 2017 Labour Party Conference in Brighton, Labour Vision published an essay in which I argued that responsible non-Jews on the Left should take note of majority Jewish opinion, and not ignore it in favour of tiny minority groups on the fringes of the Jewish community whose opinion happens to be more convenient for Leftists. What actually happened at the conference is history — and quite unpleasant history at that (for details, I recommend reading both Marcus Dysch’s overview of events and David Collier’s eyewitness account). There’s much more to be said on the topic, and I’ll get around to saying some of it before long, but for now, I’d like to revisit the odd little centrepiece of my Labour Vision essay: the analysis of signatories to four letters opposing action against antisemitism. (tl;dr: There are very few Jews who are committed anti-Zionists, but the anti-Zionist movement needs them in order to maintain the impression of not being anti-Jewish, so a lot of the same names get recycled between different open letters to the press. Also, a tutorial on how to make Euler diagrams in R. Something for everyone?)

Imaginary (Jewish) friends

It is an article of faith for many on the British Left that measures to combat left wing antisemitism are in reality measures to combat Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn: attempts promoted by the fiendish ‘Israel Lobby’, and opposed by Jews. Yes, by Jews. You know the Jews I mean: maybe not the Jews you’ve actually met, but, as Chaminda Jayanetti put it, ‘the Good Jew[s] – the Perfect Jew[s]. The Manic Pixie Dream Jew[s]. The Jew[s] to be put on a placard as evidence of how Not All Jews support Israel.’ There’s a certain kind of Leftist who needs those Jews.