Centrist dads, eh? (And presumably also centrist mums, although abusing them on behalf of the Absolute Boy might sound less like striking a feminist blow against patriarchy.) How wrong they were! They were so sure that Labour was going to lose the election, when as everyone now knows… well, actually, Labour did lose, but never mind — the centrists were still wrong. Slugs! By refusing to compromise on his left wing principles, Jeremy Corbyn shifted the Overton Window, opened up some clear red water between Labour and the Tories, and flipped social liberals for Socialism. In losing the election by a mere 55 seats out of a possible 650, he achieved total vindication for his strategy, and proved that he only has to do more of the same in order to find himself at the head of the Government after the next election (unlike — say — Gordon Brown, who lost by 48 seats and resigned, the melt). Onward, comrades! Onward to Socialism!

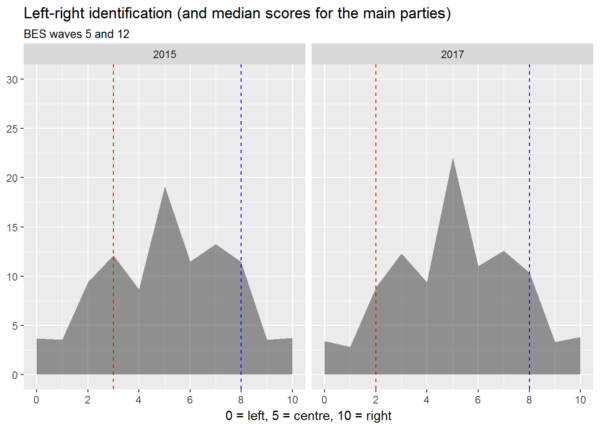

Now, I don’t believe that many people primarily choose whether or not to vote for a party to vote on the basis of how ‘left’ or ‘right’ they believe it to be. But ideas of leftness and rightness provide people with a way of summarising their relationships with political parties, and for this reason, I think it’s worth paying attention to the answers they give to survey questions about where they place themselves and the major parties on the left-right spectrum. And so we come to waves 5 and 12 of the British Election Study (or BES), in which a staggering 30725 and 34464 respondents took part immediately prior to the UK General Elections of 2015 and 2017. In the following chart, based on BES data, the grey areas show how people identified themselves, while the red and blue lines show how they typically situated the Labour Party and the Conservative Party on the same axis (respectively).1

Continue reading “The unnoticed rise of the centrist voter (and what it means for Labour)”