‘Centrists,’ Jeremy Corbyn’s former official spokesman tells us, ‘love being talked down to by people in power as it provides false reassurance that they must be better than them.’ The centrist, another Corbynite B-lister explains, ‘has the weary, lecturing tone of a frustrated parent absolutely nailed on.’ But why be so mealy mouthed? As the man who came closer than anyone to embodying the spirit of the ongoing neo-Tankie renaissance memorably put it, ‘better a thousand honest fascists than some glistening sleaze who’s “neither left nor right.”‘

Is it wise to alienate voters who don’t identify with the left or the right? Some have taken last year’s general election result to demonstrate that it is. The Hammer of the Moderates himself, Owen Jones, has argued that an appeal to moderation can make no electoral sense ‘at a time when more than 80% of the electorate voted for a left-led Labour party or the Brexiteer Tories.’ But given that Labour lost that election by a wider margin of seats than it did under Gordon Brown, that argument seems a little odd. Surely losing an election to the Conservatives after publicly abandoning the centre doesn’t indicate that publicly abandoning the centre was the right thing for Labour to do?

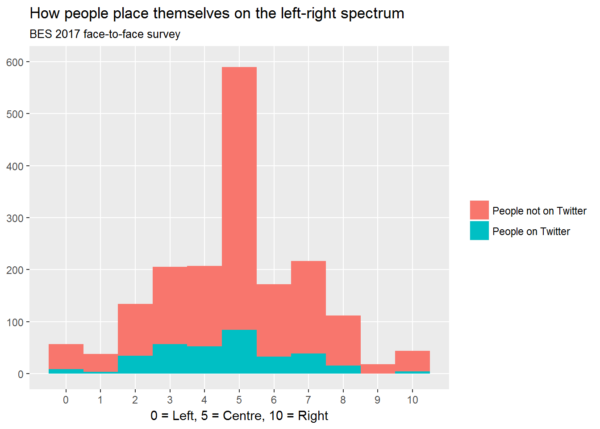

But I think I’ve got it figured out now. These people live their lives on Twitter, where the best way of getting your voice heard is to start a fight that others will want to join in. Moderation never gets much traction there. It’s not like in the outside world:

Data courtesy of the British Election Study.