This is the third and final part of my preliminary analysis of groups of voters defined by the choices they made in the 2015 general election, the 2016 European Union membership referendum, and the 2017 general election (c.f. Stephen Bush’s nine voter groups), using an English subset of responses to the British Election Study’s post-election face-to-face survey. In the first part, I looked at the ten largest groups, from Conservative-Leave-Conservative to Conservative-Remain-Labour, both in terms of their size and in terms of their self-declared likelihood to vote for various parties in future, and found that Labour Remainers were not only more numerous but (on their own assessment) more likely to be poached than Labour Leavers, while the smaller group of Conservative Remainers who had switched to voting Labour were quite likely to switch again. In the second part, I looked at six groups of voters who had in common that they could have voted but did not in the 2015 general election, finding that most of them did not vote either in the 2016 referendum or the 2017 general election, and that only the minority who voted Remain in the 2016 referendum were more likely than not to have voted in the 2017 general election.

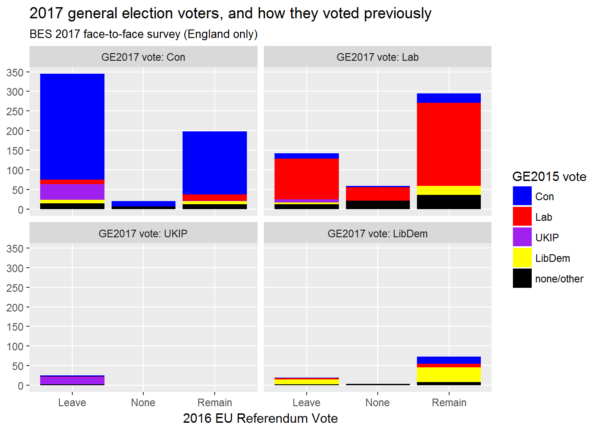

To finish up for now, here’s a single chart showing all voter groups which participated in the 2017 general election (weighted by demographic group and by 2017 vote). Each quarter of the chart below shows the members of the sample who voted for one of the four main parties. These voters are further subdivided into columns to show how they voted in the referendum and into coloured blocks to show who they voted for in 2015 (note that black covers both non-voting and voting outside the four main parties, which most often meant voting Green as the data are from England only):

Continue reading “Voters in the 2017 general election – and how they voted previously”