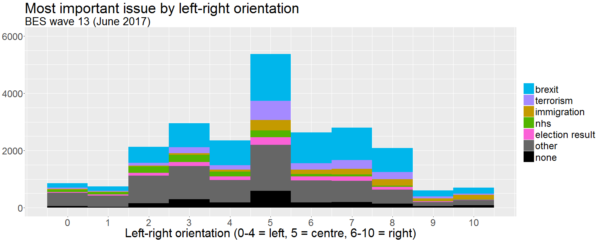

Why did people vote as they did in the June 2017 UK general election, and how might they vote in the next one — whenever it comes? One of the best sources of information on that question is wave 13 of the British Election Study: a very large survey conducted just after the election for a consortium of academics at the University of Manchester, the University of Oxford, and the University of Nottingham. Altogether 31196 respondents completed the survey, of whom 27019 (after weighting) answered the question ‘As far as you’re concerned, what is the SINGLE MOST important issue facing the country at the present time?’ and 23194 (again after weighting) identified themselves politically by positioning themselves on an eleven point scale from left to right. 21213 both placed themselves on the scale and gave their view on the most important issue. I’ve been working with this dataset for a little while, looking at how demographic variables predict perceptions of the most important issue (see my earlier post for my initial exploration of this topic), but here I’d like to focus on the association of particular issues with particular positions on the political spectrum:

Continue reading “The left, the right, the centre – and what they care about most”